Public safety app Citizen quietly redeploys controversial feature critics say encourages vigilantism, racism & paranoia

Crime-alert app Citizen has tiptoed back toward enabling what critics say would be citizen Stasi and vigilantes, quietly reactivating a controversial feature allowing its users to “report incidents right when they happen.”

Citizen, an app that sends users real-time reports of crimes in their vicinity based on a curated selection of 911 calls, has reactivated a feature that allows users to report crimes themselves, updating its website on Monday – with zero public fanfare – to add a section describing the “new feature” being tested.

User-powered crime reporting has been rife with racism, panic, and concerns users might bring about personal harm — issues not just for Citizen’s predecessor app Vigilante but also for platforms like Amazon’s Ring and Nextdoor. https://t.co/tfRBESkybf

— The Intercept (@theintercept) March 2, 2020

Spotted by the Intercept, the new page describes “protests, lost pets, downed power lines, and other community FYIs” as incidents a user might report, and stresses that a moderator reviews everything before it goes live on the app. However, the revived feature was very publicly removed back in 2017 after public outcry – and none of the issues that led to its removal have been resolved.

The app already allowed users to film crimes in progress, a feature its critics argued endangered users by encouraging them to move toward danger rather than avoid it (the stated purpose of the app). Empowering users to report an actual crime compounds that risk, especially in a culture saturated with superhero films celebrating caped crusaders delivering vigilante justice without waiting for the cops to show up.

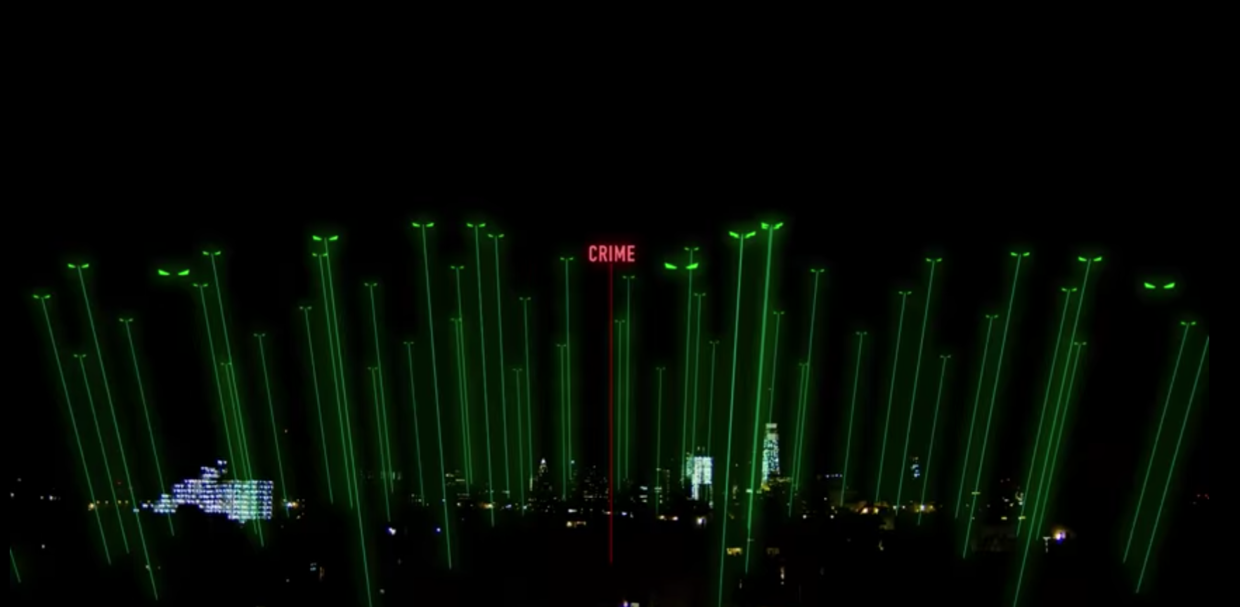

This, rather than avoiding danger, was the image the app initially embraced when it was launched as “Vigilante” back in 2016.

Citizen’s original name, plus a launch video that showed citizens ‘empowered’ by the app ganging up on an evildoer – left little doubt as to its purpose, even as a disclaimer warned users not to “interfere with the crime.” The app was panned as wildly irresponsible.

After no less than the New York Police Department issuing a statement that “Crimes in progress should be handled by the NYPD and not a vigilante with a cell phone,” a quick makeover combined with the removal of the ‘report crime’ function transformed it into Citizen.

Now that Citizen has for all intents and purposes become Vigilante again, the same problems resurface, raising the specter of an army of tech-enabled George Zimmermans stalking darker-skinned Trayvon Martins through their own Florida neighborhood.

While Citizen CEO Andrew Frame told TechCrunch on the eve of the app’s makeover that “suspicious persons” reports wouldn’t be included, privacy advocates fear giving users the power to report a crime may encourage them to snoop on those they perceive to be suspicious in the hope they commit a crime even if they don’t personally seek to interfere – turning them into a sort of citizen Stasi.

Civil liberties groups are also concerned about fanning the flames of racism and fueling fear of crime in general, even as crime rates nationwide remain low. The risk of false reports – while Citizen requires users to submit a video with every report, it would be a simple matter for pranksters to fake a crime in progress – is also high, and given the prevalence of police-involved shootings in the US, calling the police to a location can be hazardous to the health of innocent people.

The new and improved Citizen may owe the revival of its crime-report function to the normalization of crowd-sourced surveillance via devices like Amazon’s Ring doorbell, which connects users via a similar app, Neighbors, and the stand-alone surveillance-focused social network Nextdoor. Police departments that use Nextdoor in cities like Baltimore have said cautiously optimistic things about Citizen in the past year, and the shift in institutional opinion is not lost on Frame.

Observing that the police had “hated” Vigilante when it was released, he told CNN last year, “I don’t know how much they love us, but at least they don’t hate us anymore.” Citizen even hired the former NYPD communications director, J. Peter Donald, as head of policy and communications in 2018, and named former NYPD commissioner Bill Bratton to its board last year.

For an app that seems designed to enable a citizen Stasi eager to hunt down and report lawbreakers, Citizen doesn’t have much of a history of following its own rules. The Washington Post caught Citizen’s iPhone app sharing personally-identifiable data last year in violation of its own privacy policy, feeding phone numbers, emails and exact GPS coordinators to marketing data tracker Amplitude.

While Citizen supposedly removed the marketing tracker after “crime fighting app commits privacy crime against own users” was splashed across the internet, it swapped one intrusion with another in a recent update requiring location data to be “always on.” Customers denounced Citizen in app reviews as “location hungry,” “creepy,” and “hostile” until a recurrent pop-up reminder replaced the requirement.

Also on rt.com ‘Data breaches are part of life?’ Theft of list from MASSIVE privacy-annihilating facial recognition database downplayed by firmCitizen claims it “does not work with law enforcement in any way, shape or form,” though its penchant for hiring former police officials whom it refers to as “advisors with backgrounds in public safety” can certainly seem like a “formal relationship.” A recent job posting seen by the Intercept described “partners in the public sector,” implying Citizen does in fact work with some government entity, if not police departments. Either way, the treasure trove of data slurped up by such an app – including not only location and phone number but also behavior toward crime (do they walk towards it? away from it? report it themselves? film it?) – would be highly valued by any government agency.

The app is free, for now, but Citizen has raised over $40 million from venture capitalists (including the notoriously surveillance-loving Peter Thiel) and anonymous employees told Forbes in August that a future version of the app might charge universities, sports stadiums, airports, and other high-security facilities to send notifications to users during emergencies.

Police benefit, too – Bratton told Forbes that many people are leery of downloading an “official” police app, but as a privately-owned company, Citizen is more likely to see widespread adoption.

Indeed, everyone benefits from crowdsourced surveillance except the citizen-Stasi doing the reporting, as American Civil Liberties Union staff attorney Nate Wessler pointed out, albeit talking about Ring.

"It becomes this surveillance industrial complex where the people are spending their own money to send surveillance data” – data they’ve generated, in Citizen’s case – “to the police,” Wessler said.

Like this story? Share it with a friend!