Why the British should apologise to India (by Shashi Tharoor)

The centenary of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre is the right occasion for Britain to apologise for the evils of colonialism.

Two years ago, on the UK publication of my book Inglorious Empire: What The British Did to India, I took the unusual step of demanding an apology from Britain to India. I even suggested the time and place – the centenary, on April 13, 2019, of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre in Amritsar. This single event was in many ways emblematic of the worst of the “Raj”, the British Empire in India.

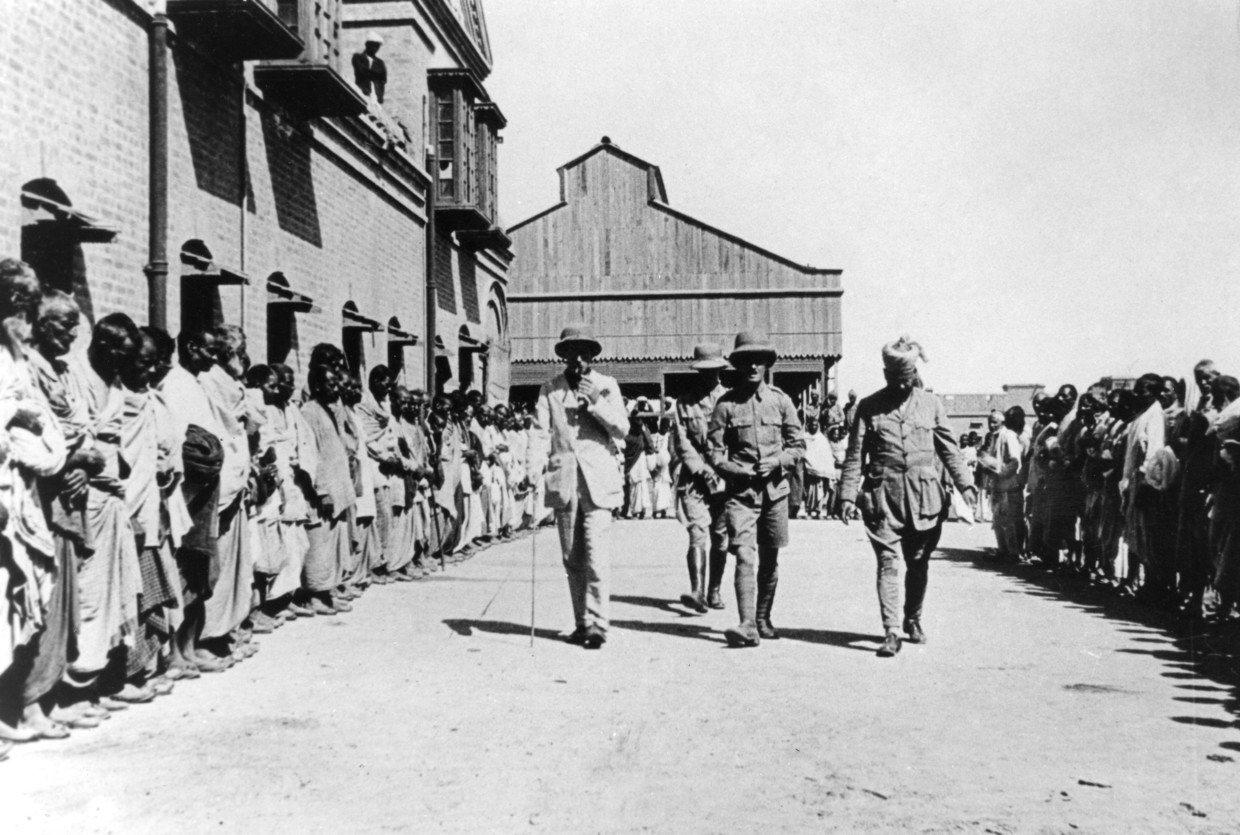

The background to the massacre lay in the British betrayal of promises to reward India for its services in the First World War. After making enormous sacrifices, and an immense contribution in men and materiel, blood and treasure, to the British war effort, Indian leaders expected to be rewarded with some measure of self-government. Those hopes were belied.

When protests broke out, the British responded with force. They arrested nationalist leaders in the city of Amritsar and opened fire on protestors, killing ten. In the riot that ensued, five Englishmen were killed and an Englishwoman assaulted (though she was rescued, and carried to safety, by Indians). Brigadier General Reginald Dyer was sent to Amritsar to restore order; he forbade demonstrations or processions, or even gathering in groups of more than three.

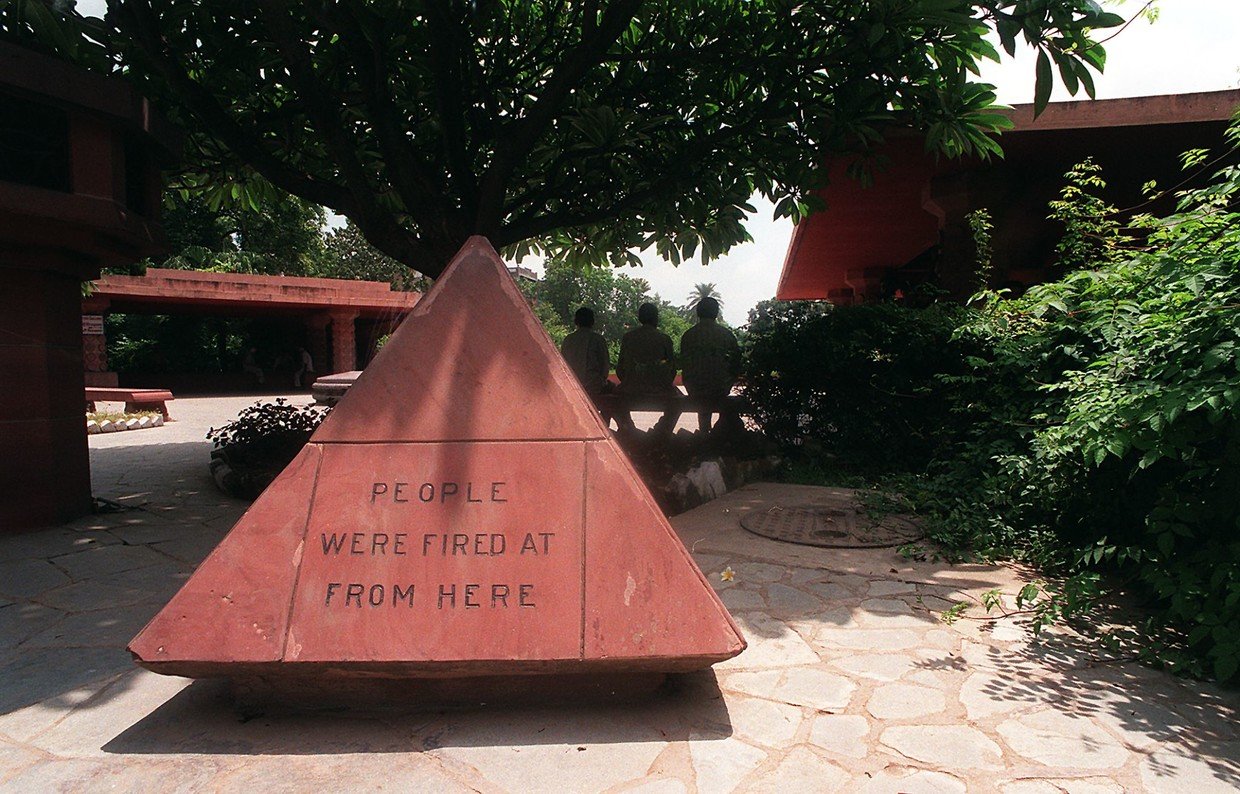

The thousands of people who had gathered in the walled garden of Jallianwala Bagh to celebrate the major religious festival of Baisakhi were unaware of this order. Dyer did not seek to find out what they were doing. He took a detachment of soldiers in armoured cars, equipped with machine-guns, and without ordering the crowd to disperse or issuing so much as a warning, ordered his troops to open fire from close quarters. They used 1,650 rounds, killed at least 379 people (the number the British were prepared to admit to; the Indian figures are considerably higher) and wounded 1,137. Barely a bullet, Dyer noted with satisfaction, was wasted.

Dyer did not order his men to fire in the air, or at the feet of their targets. They fired, on his orders, into the chests, the faces, and the wombs of the unarmed, screaming, defenceless crowd. After it was over, he refused permission for families to tend to the dead and the dying, leaving them to rot for hours in the hot sun, and inflicted numerous other humiliations on Indians, from forcing them to crawl on their bellies on a street, where an Englishwoman had been assaulted (and beating them with rifle butts if they lifted their heads), to pettier indignities like confiscating electric fans from their homes.

Dyer never showed the slightest remorse or self-doubt.

This was a “rebel meeting,” he claimed, an act of defiance of his authority that had to be punished. “It was no longer a question of merely dispersing the crowd” but one of producing a ‘moral effect’ that would ensure the Indians’ submission. He noted that he had personally directed the firing towards the five narrow exits because that was where the crowd was most dense:“the targets,” he declared, “were good.”

News of Dyer’s barbarism was suppressed by the British for six months, and when outrage at reports of his excesses mounted, an attempt was made to whitewash his sins by an official commission of enquiry, which only found him guilty of ‘grave error’. Finally, as details emerged of the horror, Dyer was relieved of his command and censured by the House of Commons, but promptly exonerated by the House of Lords and allowed to retire. Rudyard Kipling, the flatulent poetic voice of British imperialism, hailed him as ‘The Man Who Saved India’.

Even this did not strike his fellow Britons as adequate recompense for his glorious act of mass murder. They ran a public campaign for funds to honour his cruelty and collected the quite stupendous sum of £26,317, 1s 10d, worth over a quarter of a million pounds today. It was presented to him together with a jewelled sword of honour.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre was no act of insane frenzy but a conscious, deliberate imposition of colonial will. Dyer was an efficient killer rather than a crazed maniac; his was merely the evil of the unimaginative, the brutality of the military bureaucrat. But his action that Baisakhi day came to symbolize the evil of the system on whose behalf, and in whose defence, he was acting.

Everything about the incident – the betrayal of promises made to India, the cruelty of the killings, the brutality and racism that followed, the self-justification, exoneration and reward – collectively symbolized everything that was wrong about the Raj.

It represented the worst that colonialism could become, and by letting it occur, the British crossed that point of no return that exists only in the minds of men – that point which, in any unequal relationship, both ruler and subject must instinctively respect if their relationship is to survive.

The massacre made Indians out of millions of people who had not thought consciously of their political identity before that grim Sunday. It turned loyalists into nationalists and constitutionalists into agitators, led the Nobel Prize-winning poet Rabindranath Tagore to return his knighthood and a host of Indian appointees to British offices to turn in their commissions.

And above all it entrenched in Mahatma Gandhi a firm and unshakable faith in the moral righteousness of the cause of Indian independence from an empire he saw as irremediably evil, even satanic.

It is getting late for atonement, but not too late. Neither the Queen nor Theresa May were alive when the atrocity was committed, and certainly no British government of 2019 bears a shred of responsibility for that tragedy, but the nation that once allowed it to happen should atone for its past sins.

That is what German Chancellor Willy Brandt did by going onto his knees in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1970, even though as a Social Democrat he was himself a victim of Nazi persecution and innocent of any complicity in it. It is why Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologised in 2016 on behalf of Canada for the actions of his country’s authorities a century earlier in denying permission for the Indian immigrants on the Komagata Maru to land in Vancouver, thereby sending many of them to their deaths.

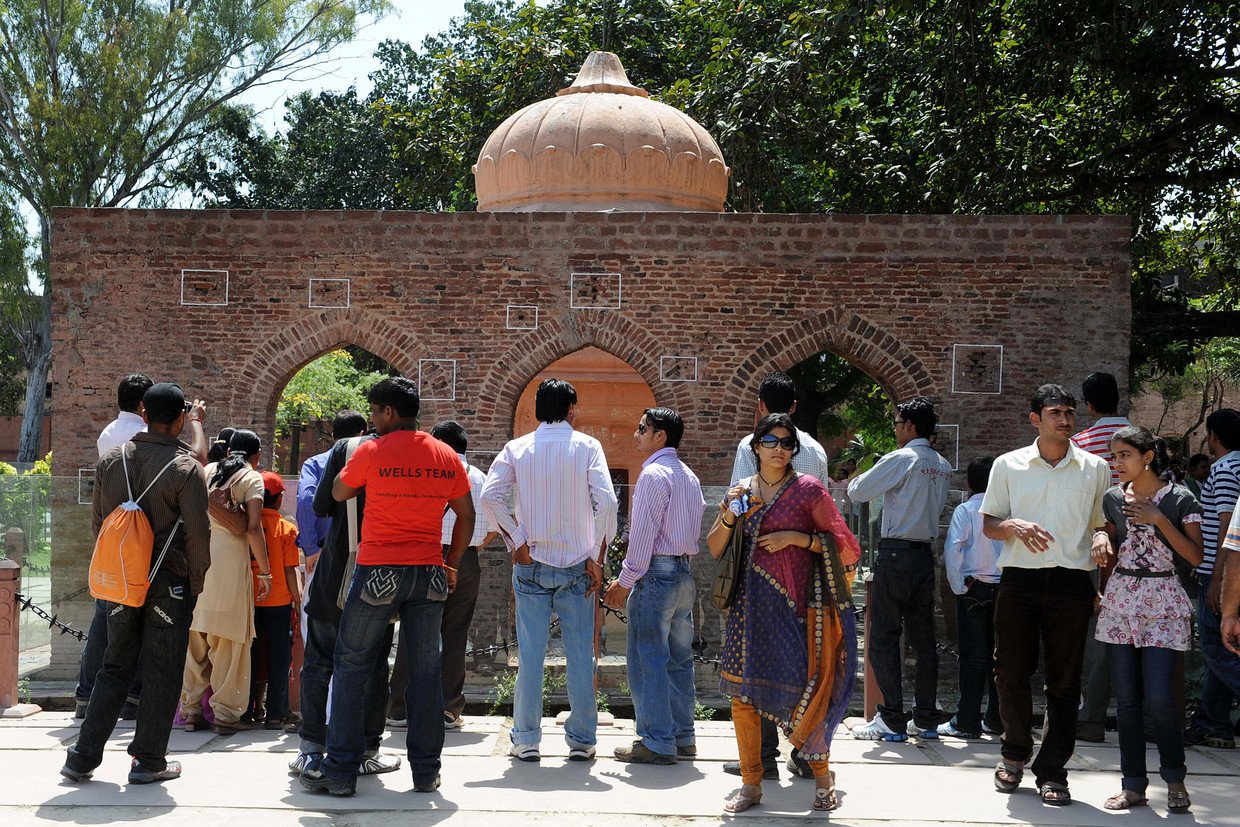

Brandt’s and Trudeau’s gracious apologies need to find their British echo. Former Prime Minister David Cameron’s rather mealy-mouthed description of the massacre in 2013 as a “deeply shameful event” is hardly an apology. Nor is the ceremonial visit to the site in 1997 by Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh, who merely left their signatures in the visitors’ book, without even a redeeming comment.

My call is for a British minister or a member of the Royal Family to find the heart, and the spirit, to get on his or her knees at Jallianwala Bagh in 2019 and apologise to the Indian people for the unforgivable massacre that was perpetrated at that site a century earlier. Along with such an apology, the British could start teaching unromanticized colonial history in their schools and decolonise their museums, which are full of looted artefacts from other countries.

The British public is woefully ignorant of the realities of the British empire, and what it meant to its subject peoples. These Brexit days have rekindled in the UK a yearning for the Raj, in gauzy romanticised television soap operas and overblown fantasies about reviving the Empire as an alternative to Europe. If British schoolchildren can learn how those dreams of the English turned out to be nightmares for their subject peoples, true atonement – of the purely moral kind, involving a serious consideration of historical responsibility rather than mere admission of guilt – might be achieved. An apology for, and at, Jallianwala Bagh would be the best place to start, and its centenary the best time to do so.

Dr. Shashi Tharoor

Dr. Shashi Tharoor is an Indian politician, author, and former international civil servant

Like this story? Share it with a friend!

Subscribe to RT newsletter to get stories the mainstream media won’t tell you.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.