As Chernobyl nuclear disaster feeds TV drama, is Ukraine looking at a real-life re-run?

This month, HBO has launched its new historical drama ‘Chernobyl’, looking back at one of the worst nuclear disasters in history – but for Ukrainians, it’s also a chilling reminder that history could repeat itself.

US cable giant HBO is reviving the 33-year-old memory of one of the worst – and the most infamous – nuclear incidents in the world. It overlays history with personal drama and intrigue in its fresh mini-series – but what the general viewer might not realize is that it’s too early for Ukraine to consign nuclear problems to history and fiction. The name ‘Chernobyl’ is being brought up again in reference to the woes plaguing Ukrainian atomic energy today.

Ukrainian nuclear power plants have become a “time bomb,” Rada member Sergey Shakhov recently said. Reactors – some of them near densely populated cities – are aging without proper oversight or funding, contracts with Russia are broken, and homegrown nuclear experts are fleeing to find better opportunities abroad.

Emergencies have plagued at least two major Ukrainian nuclear power plants, causing a series of stoppages in operations in the past three years. Some reactors at the Khmelnitsky power plant (located in a city with almost 40,000 inhabitants) had to be halted at least three times since July 2016. A main pump malfunction at the Zaporozhye power plant (close to the regional center and its 750,000+ inhabitants) forced one of its six reactors to stop in September 2018, triggering a local panic. Soon after that, two more reactors were consecutively stopped for planned repairs. They still remain halted, though one of them was supposed to be restarted early in 2019.

Those are just the instances which received attention in the media, revealed either by MPs or by nuclear plant operators.

The situation is an ecological disaster in the making, Shakhov warned in an interview to the TV channel NewsOne. Ukrainian nuclear power plants, he says, have become a “mini-Chernobyl.”

But how did a country that relies on nuclear power for 60 percent of its electricity allow its power plants to degrade so far?

Russia could help, but Kiev doesn’t want it

Ukrainian nuclear facilities were built in the Soviet Union, and for the past decades were maintained in collaboration with Russia. But after the 2014 coup, new Kiev authorities have made every effort to break up links with Moscow, including severing the nuclear cooperation agreement in 2017.

That deprived Ukraine of Russian expertise, something the aging reactors desperately need, says Stanislav Mitrakhovich, an expert on energy policy in the National Energy Security Fund (NESF) and in the Financial University under the government of the Russian Federation.

“Many power blocks are already quite old, their resources were already prolonged according to a special procedure, but this extension cannot be done infinitely. And it is not too easy to do without the help of the Russian specialist who were previously responsible for these tasks.”

Ukraine could come have up with a solution by itself, but “it should have started 10 years ago,” says Ukrainian political scientist Mikhail Pogrebinsky, the director of the Kiev Center of Political Research and Conflict Studies.

“Of course Kiev doesn’t have the money to repair and upgrade the reactors, but there are still ways to solve this. One of the most efficient ones lies in Moscow, in the Kurchatov nuclear research institute. But considering the relations, Ukraine won’t go there for help.”

The problem has fallen victim to Kiev’s politics. “Ukrainian authorities have been doing everything with political gain in mind, and that is one of the reasons things have been malfunctioning and additional risks were created for the reactors… Equipment has to be checked and maintained, and that, again, means cooperating with Russia,” says another Ukrainian political scientist, Aleksandr Dudchak.

The immediate danger

Despite the apocalyptic buzz, predicting a new Chernobyl is taking things too far, Ukrainian experts believe. The danger is no less real, however, even if it’s less dramatic in scale. The reactors might not be about to melt down and send a massive radioactive cloud billowing into the atmosphere, like Chernobyl did – instead, they will simply stop working, plunging large parts of Ukraine into a blackout.

“If Ukraine keeps to the [reactor lifespan] schedule – time’s up, switch off – it would be left without half or more generator assemblies. Sixty percent of our energy comes from nuclear power plants – this means we would have a blackout. Of course, we can’t have that, so various fictitious means are being used to prolong the lifespan,” Pogrebinsky says.

Still, the probability of a major nuclear incident – not quite the scale of Chernobyl, but comparable to the 1979 partial meltdown at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania – has been assessed at 80% within five years by researchers in a 2016 paper published in the Energy Research & Social Science academic journal.

The deadline to solve this problem is fast approaching, believes Dmitry Marunich, co-chair of the Ukrainian Energy Strategies Fund.

“There is no money, there are no contracts, the contract with [Russian nuclear energy giant] Rosatom has been broken – this is a dead-end situation that Ukrainian authorities will have to solve, and solve without delay, because under certain conditions we could have energy shortages, within five to seven to 10 years.”

International financial institutions have been supporting Ukraine with funds, but amid the more pressing day-to-day needs and the rampant corruption of the Poroshenko presidency, their effect on the restoration of dilapidated power plants is yet to be seen.

Basic incompatibilities

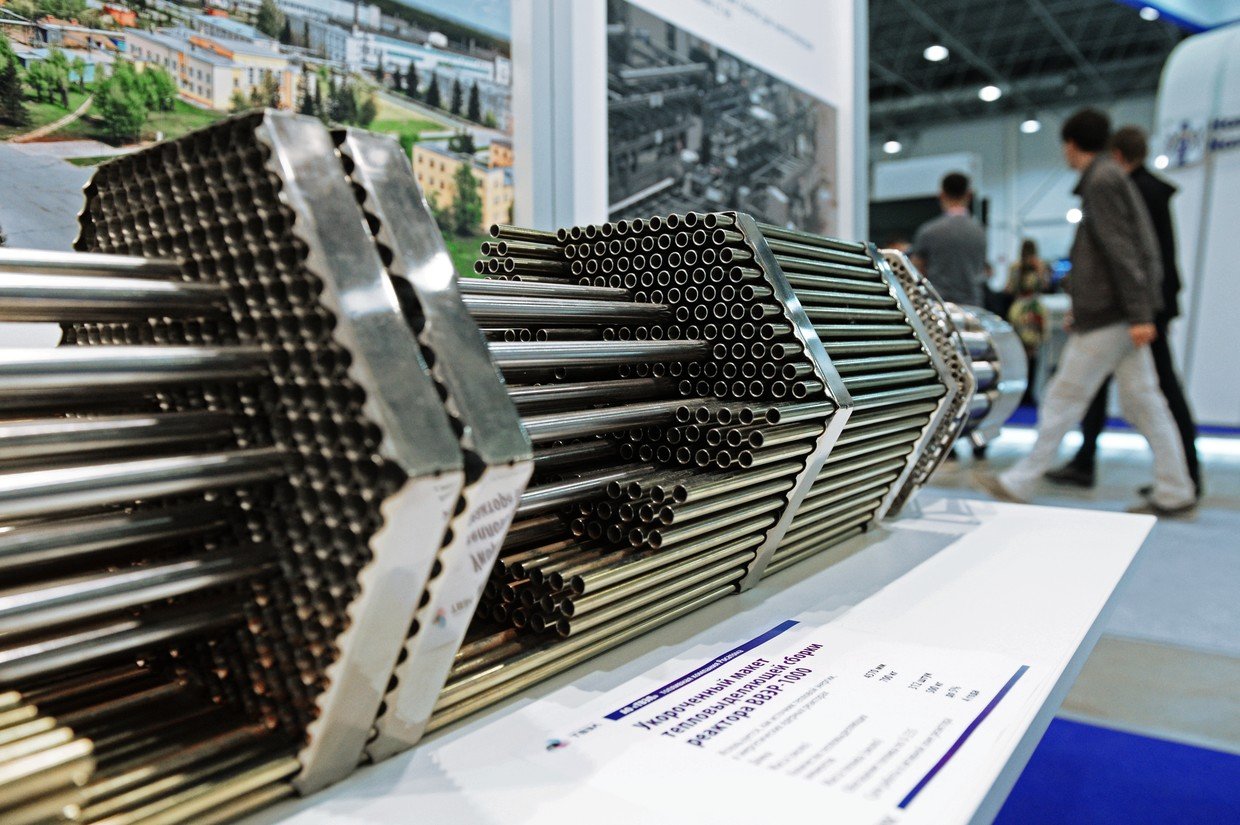

One of the main risks stems from the use of ill-fitting US-made fuel rods. Some Ukrainian power plants are fueled by fuel rods produced by the US nuclear contractor Westinghouse. They are shaped differently than those produced in Russia, and incompatibilities have caused problems before.

“Westinghouse fuel was first used in Ukrainian nuclear power plants in 2012, and even before the first fuel cycle was over it became evident they were not compatible, and the fuel assemblies had to be extracted,” Boris Martsinkevich, editor-in-chief of the Geoenergetics magazine, told RT.

Westinghouse fuel deliveries were restarted in 2015, and it’s unclear whether it’s been made more compatible with the Soviet-built equipment. If they were not, the fuel is “fully capable of halting the work of the nuclear power plants,” even though it won’t cause any mass hazardous incident.

Ukraine’s ailing economy, apart from directly depriving power plants of necessary maintenance and upgrade funds, has caused a ‘brain drain’ as collateral damage.

“Experts working at Ukrainian nuclear power plants are leaving. The situation in the country is unstable, and it’s been getting worse for five years… a lot of experts have moved out of the country, including to Russia and China, as well as other countries. Soon there’ll be no-one left to maintain the power plants,” Dudchak warns.

Irresponsible waste storage

Back when Ukraine was cooperating with Russia, Rosatom was contracted to take back and recycle spent fuel rods. Westinghouse doesn’t do that, so Kiev partnered with another US-based company – Holtec International – to build a shelter for the waste in the Chernobyl exclusion zone, effectively turning it into a radioactive dump.

The shelter, projected to go operational in late 2019 or early 2020, envisions storing nuclear waste in a concrete structure above ground, without a plan to recycle it in the future, which experts believe to be irresponsible.

“Thanks to the authorities that came to power after the coup, a site is being built in Ukraine with the help of American partners, which will store nuclear power plant waste without recycling, on the surface – that’s an insane idea,” says Dudchak.

This is complete neglect of your own citizens… simply a disaster.

“It looks like a technological and safety experiment at the cost of Ukrainians,” Mitrakhovich agrees. “But Americans promise that it will be safe.”

Promises from overseas aside, it’s ultimately up to the newly-elected authorities in Kiev whether Ukraine’s nuclear power industry gets a new lease on life or ends up being the plot fodder for another HBO show decades later.

Subscribe to RT newsletter to get stories the mainstream media won’t tell you.