Jihad against colonialism: The mysterious link between global Islam, India and the Russian Revolution

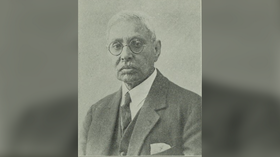

Maulana Barkatullah Bhopali, a founder member of the Ghadar Party, an early 20th century group of expatriate Indians fighting British rule, had at least two extraordinary meetings with Comrade Vladimir Lenin in the first years of Soviet power in Russia.

This changed the ideological outlook of a man who, before the outbreak of the First World War, had set up a provisional Indian government-in-exile in Kabul, of which he was the prime minister.

The Russian Revolution deeply impressed the Maulana (a term used for respected religious leaders) and he went on to become an important interface of pan-Islamism, communism and India’s freedom struggle.

He urged Muslims across the globe to unite and embrace socialism, an ideology that he felt was in line with Islamic thought, and was an ideal tool with which to crush imperialism.

The little-known story of a visionary revolutionary

The Maulana was either born in 1859 (according to his biography by Mohd Irfan) or 1862 (according to his biography by Qazi Syed Wajdi-ul-Hussaini), in the central Indian town of Bhopal, to Maulvi Shujatullah. He was a bright student and learned Urdu, Arabic and Persian languages, along with Islamic theology. During his travels, he learned English and Japanese, which helped him connect effortlessly with people – both in person and through his writings.

Bhopali was forced to flee British India in the 1880s. He was last seen in Bhopal in January 1883 and both biographers speculate that he got into trouble because of his association with Sheikh Syed Jamaluddin Afghani, a pan-Islamist in the crosshairs of the British Raj. He had apparently followed Afghani to Bombay, and made his way to England. He spent the rest of his life meeting fellow revolutionaries, cutting across class, race and nationalities.

He lived in Liverpool and London from 1880 to 1903, and then relocated in 1903 to New York, where he could take on the British more freely. Long before Netaji S.C. Bose arrived in Japan, Bhopali had made Tokyo his home from 1909 to 1914.

While in London, Bhopali launched a flurry of articles and speeches criticizing British policies, and kept in touch with fellow revolutionaries in India. He had a scholarly exchange with the poet and nationalist leader, Maulana Hasrat Mohani, who coined the slogan “Inquilab Zindabad” (Long Live the Revolution). In these letters, he stressed the need for Hindu-Muslim unity in the freedom struggle.

In Japan, he brought out a journal, The Islamic Fraternity, and later a newspaper, EI Islam, which was banned in British India. Though he had a good relationship with the Emperor of Japan, his appointment at the University of Tokyo was terminated in 1914 as a result of his activities.

Bhopali in Afghanistan

On December 1, 1915, India’s provisional government-in-exile was installed in Afghanistan with Raja Mahendra Pratap as president, Barkatullah Bhopali as prime minister, and Maulana Obaidullah Sindhi as home minister.

Bhopali had arrived in Kabul on October 3, 1915 as part of the Indo-Turkish German mission. The delegation was accommodated in a royal guest house, but the members were not allowed to step out for two months.

According to Irfan, Bhopali sent a letter to his friend, Sardar Nasrullah Khan, who was the prime minister of Afghanistan. Nasrullah urged his brother, Emir Habibullah Khan, to meet the delegation. The meeting went well. The Emir met Bhopali and Pratap separately and they discussed the formation of the provisional government of India. Once this was formed, it was decided that a letter should be sent to Czar Nicholas II seeking his help to overthrow the British colonialists in India. To show their respect for the Czar, the letter was engraved in gold.

The Czar created obstacles and leaked their secret plans. The British lodged a protest with the Afghan government. Irfan quotes a letter by Pratap dated March 28, 1966: “Emir Habibullah was upset and he asked Barkatullah Bhopali and Raja Mahendra Pratap to leave Afghanistan [in 1917].”

After Emir Habibullah Khan’s assassination in February 1919, his son Amanullah Khan declared war on the British rulers. Soviet Russia indirectly supported Afghanistan in this war, and was the first country to establish diplomatic ties with it. Amanullah Khan sent for Bhopali, and appointed him the ambassador of Afghanistan to Russia.

Indian revolutionary in a revolutionary Russia

In an essay on “Indian Freedom Fighters in Tashkent (1918–1922),” Dilorom Karomat notes that Pratap and Bhopali were among the first group of Indian nationalists to establish contact with the new Bolshevik government.

According to Karomat, “Lenin attracted Indian freedom fighters as his ideas greatly influenced the growing movement for independence in India. Lenin corresponded and had discussions with several prominent Indian revolutionaries like Mohammad Barkatullah (1859–1927) … and was well informed about campaigns of non-cooperation. India was seen by Lenin as one of the greatest countries of Asia, which would play a leading role in the fighting against imperialist colonial systems in the East.”

Maulana first met Lenin on November 23, 1918. On behalf of the Indian people, he presented Lenin with a walking stick made of sandalwood, and sought Lenin’s help in India’s freedom struggle.

Bhopali called Lenin “The Shining Sun,” and subsequently wrote several articles on him and his philosophy.

In his speech at the meeting of the RSFSR All-Russian Central Executive Committee, he said, “Comrades and brothers, leaders of the Russian Revolution! India sends its greetings from afar for the victory you have achieved in the name of global progress and the entire proletariat. India bows before the great destiny that has befallen Russia. India prays and implores Providence to send you the strength to carry on the work you have begun to its conclusion, and for your ideas to spread throughout the world. The revolution in Russia has made a profound impression on the psyche of the Indian people. Despite all of England’s efforts, the slogan of self-determination of nations has penetrated into India.”

In her essay, “India’s First Envoys to Revolutionary Russia” (in “The Russian Revolution and India”), Irina Avchina reveals that the envoys of India met Lenin in November 1918, and used false names “in an attempt to throw the British intelligence service off their track.” They called themselves “Muhammed Hadi and Ahmad Haris.” The former was an alias used by Bhopali, according to Irfan’s biography, ‘Barkatullah Bhopali’.

On November 26, 1918, Izvestia carried a news report about an Indian delegation meeting the chairman of the All-Russian Central Committee, Yakov Mikhailovich Sverdlov, and presenting him with a memorandum that was scathing in its condemnation of British rule in India. They hoped that the brothers of “Russia will extend their hand to us in the liberation of India.”

Bhopali reached Tashkent in March 1919. Karomat notes that, according to the local newspaper, Ishtrokiun, Bhopali had met with the Emir of Bukhara first, which was seen as politically important and secret. The same newspaper published his “Address to All Muslims of Asia” (March 22, 1919), as well as “Bolshevik Ideas and Islamic Republic” (April 14, 1919).”

Karomat emphasizes that Pratap and Bhopali “met Lenin and discussed many issues related to obtaining freedom by India.”

According to Wajdi-ul-Hussaini, when Bhopali visited Moscow for the second time in 1919, he was given a rousing welcome. He held meetings with Lenin and sought his help in India’s freedom struggle. He quotes a compatriot of the Maulana on the May 7, 1919 meeting with Lenin asking Bhopali, “Which language should I speak in?”

Bhopali also used his time in 1919 to travel in the Volga region and visit several cities. Bhopal-based history enthusiast Rizwanuddin Ansari says a street in Ufa has been named in Bhopali’s memory: “Few people know of this street in Ufa. Lenin had sent the Maulana to Ufa as his special envoy to speak to the Bashkirs, the Muslim natives of Bashkortostan.” However, this street is today untraceable and no Russian source mentions it. Bhopali spoke at the Red Army Club on November 4, 1919, and the building that housed it now bears a memorial plaque.

Forgotten hero

Bhopali’s legacy has not been preserved in the annals of India’s or Russia’s history with the attention it deserves, even though a couple of books and an occasional article have been written about his fiery revolutionism.Forgotten is the fact that Bhopali set up a government-in-exile decades before Indian revolutionary Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose in the Japan-occupied Andaman and Nicobar Islands in 1943.

The two best-known and oldest books on Bhopali are in Urdu, by Irfan and Wajdi-ul-Hussaini. A Hindi translation of the latter was commissioned by the Madhya Pradesh Urdu Academy in 1989, and Syed Iftikhar Ali undertook a “liberal” translation of Irfan’s book into English.

While Irfan was the first to put the spotlight on Bhopali, Wajid-ul-Hussaini offers a spectacular account of Maulana’s transformation from a respected intellectual to a fervent revolutionary.

Impressed with Lenin and Russian policies, Bhopali wrote an article in the Turkish language inviting Islamic intellectuals to join him. Wajdi-ul-Hussaini quotes from it: “O Muslims, do not believe in America, England or France. Their treachery and deceit are evident in the division of Iran, Afghanistan and the Ottoman Empire and the capture of Istanbul. Britain and France had made a secret treaty with the Czar … and Comrade Lenin exposed this treaty … and established the rule of the people.”

Samee Nasim Siddiqui, an academic who wrote a research paper on “The Career of Muhammad Barkatullah (1864-1927): From Intellectual to Anti-Colonial Revolutionary,” offers a detailed account.

Siddiqui states that Bhopali wrote a booklet titled “Bolshevism and the Islamic Body Politic” to recruit Muslims around the world. “Oh Mohammedans! Listen to this divine cry. Respond to this call of liberty, equality and brotherhood which Brother Lenin and the Soviet Government of Russia and all eastern countries [have given], we are announcing to you that the secret treaties made between the deposed Emperor and other States as regards the occupation of Constantinople, as well as treaties ratified by the dismissed Kerensky, have been annulled and torn up. The Russian Soviet, therefore, considers it essential that Constantinople should remain in the hands of the Muslims,” Bhopali wrote in the booklet.

He saw no contradiction between socialism and Islam. “While he openly stated he was neither a communist or a socialist, his anti-colonialism and Bolshevik calls for revolution based on equality and liberty were compatible. And, indeed, looking back at his early writings, criticism of capitalist greed, the destruction of industry in India, and the treatment of the lower classes by the British were part of his critique of British rule well before he could have even foreseen an alliance with the Bolsheviks,” adds Siddiqui.

Maulana’s legacy

Wajdi-ul-Hussaini and Irfan noted that secret agent Sidney Reilly had invited Bhopali to join and head the Turkistan Ulema delegation to India and the Middle East, and to speak against the Bolsheviks.

Bhopali rejected the offer. “I have been sincerely struggling all my life for the independence of my country. Today, I regret that my attempts did not succeed. But at the same time I am also satisfied that hundreds and thousands of others who have followed me are brave and truthful. With satisfaction I will place the destiny of my beloved nation in their hands. I have no desire to go down in history as a traitor to my country. You may easily find others who will gladly join you. Leave me alone,” Wajdi-ul-Hussaini recorded in his book.

The opening of the Tashkent Military School didn’t go down well in British circles. “The Times of London wrote in its issue of 16 January 1920 that the Bolsheviks had opened a large number of propaganda schools at Tashkent from where agents will be sent to India, China and all Muslim countries. This type of propaganda continued even up to February 1921 when the political school at Tashkent and the military training school for Indians had been wound up and Indian revolutionaries moved to Moscow,” Karomat noted.

With the closure of the Military School in May 1921, Tashkent ceased to be a Soviet-sponsored base for Indian freedom fighters.

Bhopali left Moscow in the summer of 1922 after he fell seriously ill. In a letter dated March 28, 1966, Mahendra Pratap tells Irfan that Bhopali had left for Berlin, where he stayed for some time on account of his ill health.

When he died in San Francisco on September 20, 1927, the United States of India, a publication of the Ghadar Party in the US, paid a glowing tribute: “His death is a grave loss to India in that it constitutes a severe blow to the revolutionary movement whose main pillar he had been for more than thirty years. The loss will not easily be forgotten, nor will the gap created soon be filled. Heroes like Barkatullah are not born everyday.”

Ansari, the history enthusiast, added: “It’s a good thing that Arjun Singh [former chief minister of Madhya Pradesh] decided to rename Bhopal University as Barkatullah University in 1988, or this brilliant orator and erudite scholar who changed the political landscape with his fiery speeches and revolutionary writings, would have been long forgotten in his hometown too.”

Razia Tanveer, Wajdi-ul-Hussaini’s daughter, who grew up on tales of the Maulana’s incredible mission, says Bhopali’s journey is important as it underlines the role of Muslims in India’s freedom struggle, and how they embraced socialism to overthrow the colonialists. “This is a story that needs to be preserved in all its glory,” she asserts.