The colonial legacy of this vital river threatens peace in Africa and beyond

This past summer, a significant and somewhat unexpected development occurred when the parliament of South Sudan ratified the Nile Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA), also known as the Entebbe Agreement. Some 14 years after several East African countries initially signed the agreement, the ratification of the document officially called into question Egypt and Sudan’s historic rights to the water of the Nile.

The Entebbe Agreement was originally signed in 2010 by Ethiopia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya, and Burundi. South Sudan joined the agreement in 2012. However, a key provision required the document to be ratified by the parliaments of at least six countries in order to establish a special commission that would be permanently headquartered in Uganda. After South Sudan ratified the document, the necessary quorum was finally achieved.

On October 13, Ethiopia officially announced that the agreement had entered into force. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed described this moment as a “historic milestone” in the collective efforts of the signatory countries to “foster genuine cooperation in the Nile Basin.”

The Entebbe Agreement nullifies the historical water allocations to Egypt and Sudan (55.5 billion cubic meters annually for Egypt and 18.5 billion cubic meters for Sudan), determined by colonial-era agreements from 1929 and the 1959 Agreement “for the full utilization of the Nile waters” between the two countries.

Who owns the Nile?

A total of 12 African countries are located in the Nile Basin: Burundi, Egypt, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Sudan, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, the Central African Republic, Eritrea, and Ethiopia. Together, these nations are home to 40% of Africa’s total population.

Known as the longest river in Africa (and possibly in the world), the Nile competes only with the Amazon in terms of length. It stretches approximately 5,600km from Lake Victoria, where the White Nile originates, to the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile Basin covers an area of 3.4 million square kilometers. The Blue Nile, which begins in Ethiopia, merges with the White Nile in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, before flowing into the Mediterranean Sea via Egypt.

Since ancient times, the waters of the Nile have been used for irrigation and, today, they play a crucial role in electricity generation. The Nile is particularly important for Egypt – 95% of its population resides along the banks of the river and in the Nile Delta. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus famously referred to Egypt as “the gift of the Nile.” Major Egyptian cities, including the capital Cairo and Alexandria, are situated along the banks of this river.

Currently, official statistics indicate that Egypt faces a water deficit of up to 20 billion cubic meters per year, while its total annual water requirements reach 80 billion cubic meters. The country’s economy relies heavily on the Nile, with approximately 97% of its water supply coming from this river.

Though Egypt lies downstream, colonial-era agreements still grant it not only a larger share of the river’s water but also the authority to oppose the construction of dams and other water projects in upstream states. As a result, economic development in these countries poses a threat to Egypt’s water needs. Interestingly, about 85% of the water that flows into the Nile comes from the Ethiopian highlands, yet Ethiopia can use only 1% of that volume of water.

Colonial agreements

The historical agreements on the Nile Basin date back to the colonial era, when powers like Britain, Italy, and France controlled much of Africa. For example, a protocol between Britain and Italy outlined and allocated rights to use the waters of the Atbarah River, a major tributary of the Nile located in present-day Sudan and Ethiopia.

Among the major agreements concerning the Nile Basin is the 1929 document signed between Egypt and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan – a condominium jointly administered by Egypt and Britain from 1899 until 1956. This treaty guaranteed Egypt a specific share of the river’s waters, and was referred to in the document as Egypt’s “historical right.” It also granted Cairo the authority to object to any construction on the Nile’s tributaries if it deemed such projects a threat to its water security.

The rights of other countries to water

In 1959, Egypt, which had officially gained independence after the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1922, and Sudan, which became independent from Britain and Egypt in 1956, signed a new agreement for the complete control and use of the Nile waters. It was based on the 1929 agreement, and outlined precise water allocations for each country: Egypt secured the right to use 55 billion cubic meters of water per year, while Sudan obtained 18.5 billion cubic meters. This document was influenced by the projects that the countries planned to implement: Egypt intended to construct the Aswan High Dam, while Sudan planned to build the Roseires Dam on the Blue Nile.

At that time, upstream countries were still colonies and did not participate in the agreement. For instance, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi gained independence only in 1962, and Kenya did so in 1963. Understandably, these nations now take a firm stance against agreements made before they became independent. Since they didn’t sign these documents in the post-colonial era, they do not recognize them as binding. As for Ethiopia, which was never colonized, it has consistently rejected the 1929 and 1959 agreements, arguing that they ignored its interests. Essentially, these agreements granted Egypt absolute control over Nile waters and disregarded the rights of other countries in the Nile Basin and their need to use water resources for development.

This led to significant disagreements about addressing water issues in the Nile Basin and finding a common vision. In recent years, tensions have increased between Egypt and Ethiopia. Despite the absence of agreements with Cairo and Khartoum, Ethiopia is currently completing the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile. Previous trilateral negotiations involving international mediators have stalled. On September 8, 2023, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed announced the completion of the fourth and final filling of the dam’s reservoir, an action that Egypt viewed as a blatant violation of international law.

Ethiopia is the second-most populous country in Africa after Nigeria and is home to over 120 million people, nearly half of whom lack access to electricity. Currently, around 90% of Ethiopia’s electricity generation comes from hydropower. Since 2022, GERD has generated 1,550 MW, and may ultimately produce over 5,000 MW, with the current total installed electricity generation capacity in the country amounting to 5,200 MW. In contrast, Egypt, with a population of approximately 110 million, is one of the continent’s leading electricity producers. In 2022-2023, Egypt’s total installed electricity generation capacity surpassed 59,000 MW, and the entire population has access to electricity. About 80% of Egypt’s electricity generation comes from fossil fuels (natural gas), and about 7% from hydropower. Additionally, Egypt exports LNG to various countries, including Europe.

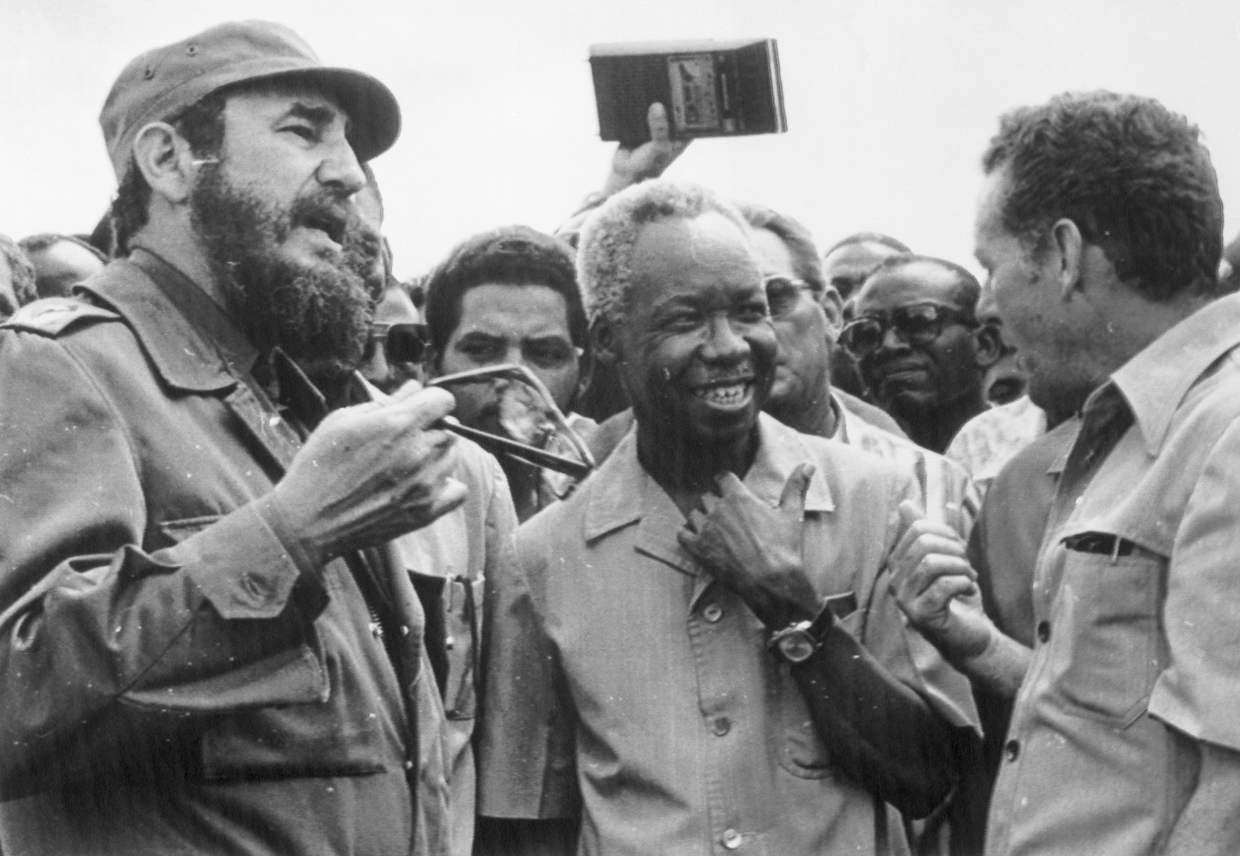

The Nyerere principle

Upstream nations adhere to the “clean slate” theory, known as the “Julius Nyerere Principle,” named after Tanzania’s first president (1964-1985). When he took office, Nyerere wrote a letter to former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, stating that Tanzania would not recognize agreements signed during colonial times, particularly those concerning the Nile, which mandated upstream countries to notify downstream states about any projects they intended to undertake. This approach was later adopted by Burundi, Uganda, and Kenya, and became known as the Nyerere Principle.

By contrast, Egypt has maintained the principle of international law known as “Uti possidetis juris,” which asserts that countries should respect the borders and agreements that existed in colonial times prior to their independence, in order to avoid conflicts and wars.

Upstream Nile countries have adopted Nyerere’s principle and refuse to follow agreements established during the colonial era. The Entebbe Agreement includes the phrase “fair use,” which also embodies Nyerere’s idea. Notably, this principle aligns with the 1997 UN Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, which calls to establish a binding legal framework that would define the usage of resources and establish mechanisms for resolving disputes.

Searching for solutions

In the second half of the 20th century, numerous initiatives aimed at fostering regional cooperation in the Nile Basin were proposed. However, most of these documents were focused on technical aspects and failed to address the dependence of the Nile Basin countries on Egypt and Sudan regarding water resource management. One such initiative was the 1967 Hydro-meteorological Survey of the Catchments of Lakes Victoria, Kyoga and Albert (the HYDROMET project), supported by the UN Development Program (UNDP) and Egypt. This project arose in response to a significant rise in Lake Victoria’s water levels in the early 1960s, which led to severe flooding. Over 25 years, substantial work was done to gather hydrometeorological data and train a skilled group of regional experts. Additionally, a regional forum was established to allow participants to discuss technical issues related to the Nile Basin. Interestingly, Ethiopia did not participate in the project from the outset.

In 1992, water resource ministers from five Nile Basin countries (Egypt, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda) along with representatives from the US established Technical Cooperation Committee for the Promotion of the Development and Environmental Protection of the Nile River Basin (TECCONILE). The Democratic Republic of the Congo and other upstream nations remained observers. The committee was viewed as a transitional plan with a three-year timeline, on the basis of which a permanent institution was supposed to be created. Just like HYDROMET, however, TECCONILE focused on technical aspects.

In 1999, nine countries – Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda, and the DRC – officially launched the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), with Eritrea joining as an observer. The initiative aimed to establish partnerships among nations located along the Nile that would be based on mutually beneficial cooperation, and to promote regional peace and security. The World Bank and other international organizations supported this initiative.

The Entebbe Agreement

In May 2010, six upstream countries – Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Burundi, and Rwanda – signed a framework agreement in Entebbe, Uganda, which became known as the Entebbe Agreement. South Sudan joined in 2012. This document effectively nullified Egypt and Sudan’s historical water quotas outlined in the 1929 and 1959 agreements.

The Entebbe Agreement required the document to be ratified by the parliaments of at least six nations before the Nile Basin Commission, with permanent headquarters in Uganda, could be established. This commission would legally oversee the rights and responsibilities related to the Nile Basin Initiative while ensuring cooperation among member states on the sustainable and equitable management of water resources, moving beyond the previously dominant quota system.

Ethiopia has been the most proactive champion of this initiative. For a long time, work on the agreement stalled. Ethiopia and Rwanda became the first nations to ratify it in 2013. Tanzania followed in 2015, Uganda in 2019, and Burundi ratified the agreement in 2023.

To come into force, the agreement required ratification by six countries, and South Sudan became the sixth nation to approve the Entebbe Agreement on July 25, 2024, 14 years after it was initially signed. Kenya remains the only signatory whose parliament has yet to ratify the agreement.

What’s next?

According to the text of the agreement, the document will come into force exactly 60 days after the sixth country ratifies it. In October, Uganda is scheduled to host the Second Nile Summit (the first was held in 2017), where upstream Nile countries will gather to celebrate the entry into force of the historic Cooperative Framework Agreement and the establishment of the Nile Basin Commission.

However, these developments only add to the long-standing tensions between Egypt and Ethiopia, which extend beyond the issue of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). At the beginning of 2024, the situation escalated dramatically after the Memorandum of Understanding was signed between Ethiopia and the unrecognized region of Somaliland on January 1. This agreement enabled Ethiopia to gain access to the Red Sea via the port of Berbera in exchange for potentially recognizing Somaliland.

Egypt has firmly backed the official Somali authorities, which have been outraged by the unilateral actions of the breakaway region. In August 2024, President of Somalia Hassan Sheikh Mohamud visited Cairo, where Egypt and Somalia signed a bilateral defense cooperation agreement. Following this, Egypt started supplying military aid to Somalia, demonstrating that it is prepared for a potential armed conflict with Ethiopia, in which Somalia may be used as a staging area.

Meanwhile, as the situation in the Nile Basin has shown, Ethiopia is not about to back down. Therefore, while the Entebbe Agreement aims to establish equality among nations and rectify colonial-era mistakes, it paradoxically heightens the likelihood of a renewed confrontation in East Africa, pitting two regional heavyweights – Egypt and Ethiopia – against each other.